Shortly after Kwarteng’s £45 bn “mini” budget announcement, a sharp market-sell off occurred, as investors believed they should be compensated more for the risk they’re taking investing in the UK economy. Prices of long-term gilts suffered, especially for 30-year bonds whose yield rose from 3.48% to 5%, within a matter of days.

When interest rates rise, bond prices fall (and vice-versa), with long-maturity bonds most sensitive to rate changes (or interest rate risk). This is because longer-term bonds have a greater duration than short-term bonds that are closer to maturity and have fewer coupon payments remaining.

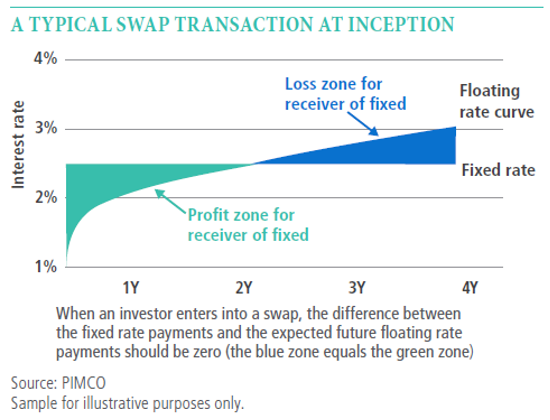

Pension funds have an obligation to pay a stream of retirement cash flows in the far future (c. 30y) to their policyholders and this naturally exposes pension funds to c. 30y interest rate risk. Therefore, a large proportion of the UK’s pension schemes, specifically ‘Defined Benefit’, will have chosen to hedge interest rate risk, using a very convenient ‘derivative’ called interest rate swaps; Interest rate swaps involve two parties – one which receives a stream of future payments based on a fixed interest rate, in exchange for its obligation to pay a set of future payments to the other party, that are based on a floating interest rate (LIBOR). What’s attractive about swaps is that there is no principal investment up front, and so this cash that would’ve been invested in long dated safe bonds has now been placed in other liquid assets (e.g., stocks, EMs) and shorter-dated gilts.

These pension schemes manage these swaps (and other gilt derivatives) by so-called liability-driven investment (LDI) funds. Long-dated bonds represent around two-thirds of Britain’s roughly £1.5 trillion in LDIs. When yields go up too far and too fast, the schemes need to provide more cash (or collateral) to the LDI funds because their positions become loss-making – they are paying out more money in the transaction (e.g interest rate swaps) than they are receiving – this process is known as a margin call. Therefore, this sharp rise in the yield of long-dated gilts, this week, led UK pension funds to have been hit with margin calls of as much as £100 million each, by the LDI funds. The Figure below illustrates the profit and loss LDIs can incur through fluctuations in the floating interest rate.

Therefore, UK pension schemes started selling off their liquid assets and gilts, to raise cash to meet margin calls to try and avoid insolvency, or they were kicked out of their positions because they could not pay up in time. This went on to put even more pressure on the gilt market as well as equities market, with the FTSE 250 falling more 5% this week.

The BoE announced its temporary programme of bond purchases to stave off an imminent crash in the gilt market, by pledging unlimited purchases of long-dated bonds. Thus far, the bank said it would kick-off the plan by buying up to £5 billion of long-dated gilts (those with a maturity of more than 20 years) – these operations will continue every weekday until Oct. 14 and after today’s auction, that means the bailout could reach £61 billion. This has forced down the yields of long-dated gilts, particularly the 30-year bond, whose yield fell from 5.5% (after the tax-cut announcement) to 4%.

However, those gains ensued heavy losses for global bond markets, since last Friday, as the heavy sell-off in gilts spread around the world. These significant swings in the gilt market, have sent shockwaves through the European and US bond market, and it will be interesting to see the degree to which they will be affected.

Appendix:

Defined Benefit pension scheme: A retirement income based on your salary and the number of years you’ve worked for the employer, rather than the amount of money you’ve contributed to the pension.

Analyst: William Nakhoul

Continue with Facebook Continue with Google