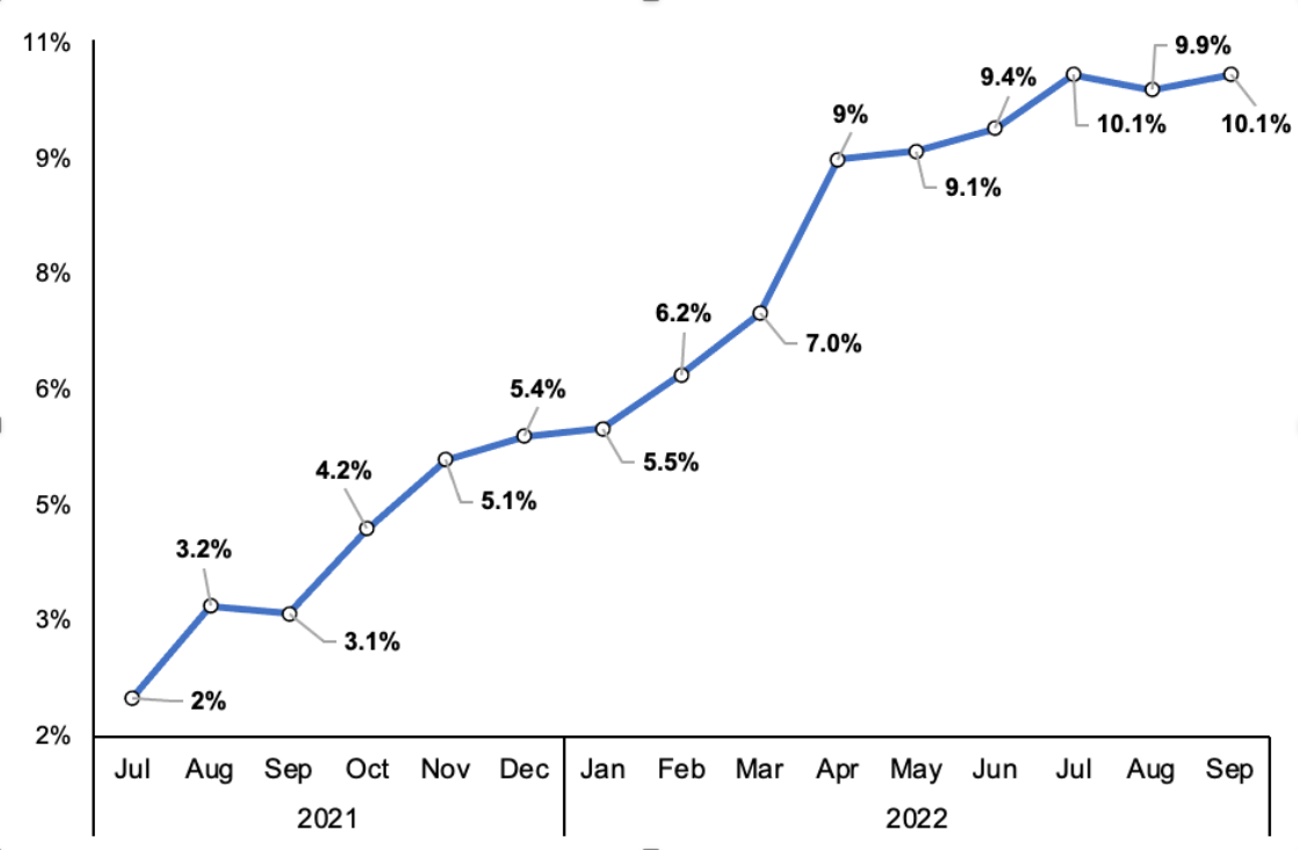

As the UK’s inflation rate hit a 40-year high of 10.1% in September, there’s one word that everyone has been asking: why?

The current inflation landscape

Source: Office for National Statistics

While soaring food prices and the taunting energy crisis hammer the UK economy, there lacks an accepted explanation for the persistent rise in inflation rates since mid-2021. Especially after years of undershooting the inflation target, a break from the norm through inflation overshooting has been underplayed until only quite recently. Speaking to the BBC, Former Bank of England Governor Mervyn King loudly voiced his opinions on the inherent inflation driver while live on BBC: “That was a mistake. That led to inflation.” Who was he directing these accusations towards? Quantitative easing, he claims, is the culprit.

How does the quantitative easing mechanism work?

Quantitative easing, also known as “QE”, describes the process whereby the central bank (in this case, the Bank of England) purchases bonds from the secondary market. As QE is often implemented as a response to a Keynesian liquidity trap, the record-low 0.1% bank rate during the COVID pandemic expedited the heavy QE usage by the Bank of England.

The mechanisms of quantitative easing can be broken down into two core mechanisms: the liquidity effect and the yield curve effect.

The liquidity effect boosts market liquidity by injecting bank reserves. The central bank buys UK government bonds or corporate bonds from other financial companies and pension funds. This exchanges bonds (which are illiquid assets) for cash (which are liquid assets) so the financial institutions have higher liquidity to lend out more money. As the banking liquidity has risen, they can therefore reduce their interest rates, which encourages greater borrowing and investment.

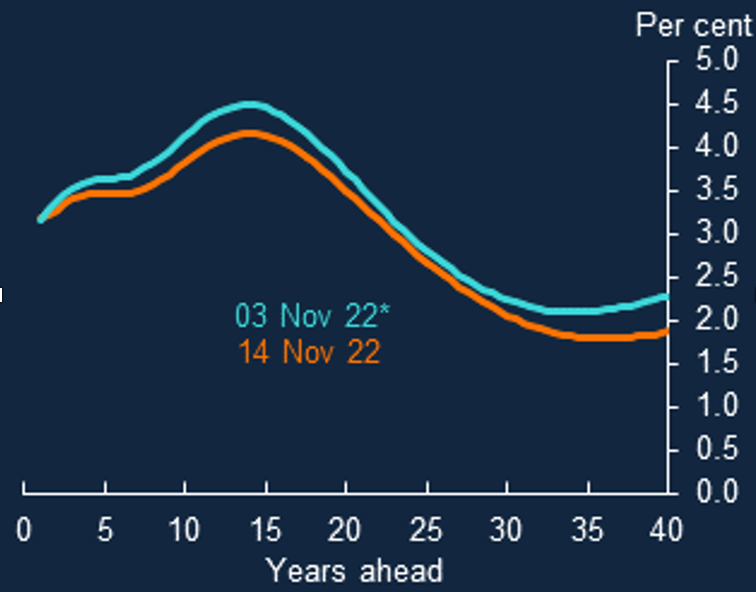

The yield curve effect pushes down yields on long-term nominal assets, including government and corporate bonds. Through an increase in purchases of longer-maturity bonds, the prices of these bonds are therefore driven upwards. As the coupon rate of bonds is fixed, the current yield of these bonds will fall due to their inverse relationship with their prices. This leads to a diagrammatical dip of longer-maturity bonds on the yield curve, a line that plots yields of bonds having equal credit quality but differing maturity dates. As seen on the graph below, the UK bonds for November 2022 form a humped yield curve, a curvature that often implies an uncertain economic situation. As the yield of longer-maturity bonds has fallen, the demand for these bonds will fall as the relative return has fallen, encouraging investors to sell off their government bonds. The investors can then re-invest their capital away from longer-term assets and into shorter-term assets, which will spur economic growth.

These mechanisms stimulate the economy by funnelling through several other channels: monetary policy signalling, where extra information is conveyed about lowering the future path of interest rates; portfolio rebalancing, where a switch away from longer-maturity binds into higher risk assets is induced; exchange rate, where the price of domestic assets relative to overseas assets is lowered from hot money outflows; and confidence, where the amount of volatility and uncertainty in markets is reduced. However, if quantitative easing is excessively employed, an overstimulation of the economy through boosted liquidity, lending, and confidence can lead to spikes in the inflation rate.

What is happening to QE and the inflation outlook?

At the dawn of November, the Bank of England became the first central bank among major economies to start successfully auctioning its accumulated stockpile of gilts by selling £750 million worth of UK government bonds. In total, the Bank of England has set a goal to sell £6 billion of gilts across eight auctions in November and December, a component of their wider plan to reduce its gilt holdings by £80 billion over the next 12 months through both sales and reserving the payments from maturing gilts.

Despite this mild form of quantitative tightening, Huw Pill – the current Chief Economist at the Bank of England – stated there was “still more to do” to tackle the impending inflation spikes, a week after the Bank of England raised interest rates by 0.75 basis points to 3%.

However, the inflationary outlook is not all negative. In the US, the inflation rate slowed to 7.7% in the year to October after the Federal Reserve reduced its benchmark interest rate, leading to a fall from the 8.2% inflation recorded a month earlier. As the odds for another 75 basis points rate hike from the Federal Reserve are now below 20% (down from nearly 70% a month ago), UK market confidence rose as the two market interest rates have historically moved in tandem. Consequently, the sterling rose sharply to just over $1.16 following the news of the surprise cooling in US inflation. Though the lower inflation is unlikely to be immediately replicated by the UK economy, it is just a matter of time until we follow in the footsteps of the US.

Appendix:

Bank Rate: The interest rate that other banks pay on loans they take out from the Bank of England.

Basis Points: A common unit of measurement for changes in financial percentages. A 0.01% change is the same as 1 basis point.

Bonds: An investment security where an investor lends money to a company or a government for a set period of time (maturity period), in exchange for regular interest payments.

Current Yield: The bond’s annual payment divided by the current price of the bond.

Gilts: A term for bonds that are issued by the British government.

Hot Money Outflows: A fall in the exchange rate as foreign investors store fewer holdings abroad due to lower interest rates, which thereby reduces demand for domestic currency.

Inflation: An increase in the general price level of goods/services within an economy.

Liquidity Trap: When expansionary monetary policy fails to stimulate aggregate demand after a period of very low interest rates and high amounts of cash balances held by households and businesses.

Quantitative Tightening: The operation of removing liquidity by selling bonds into the secondary market or by allowing the bonds that it holds on its balance sheet to mature without replacing the full amount.

Analyst: Kangzi Chan

Continue with Facebook Continue with Google